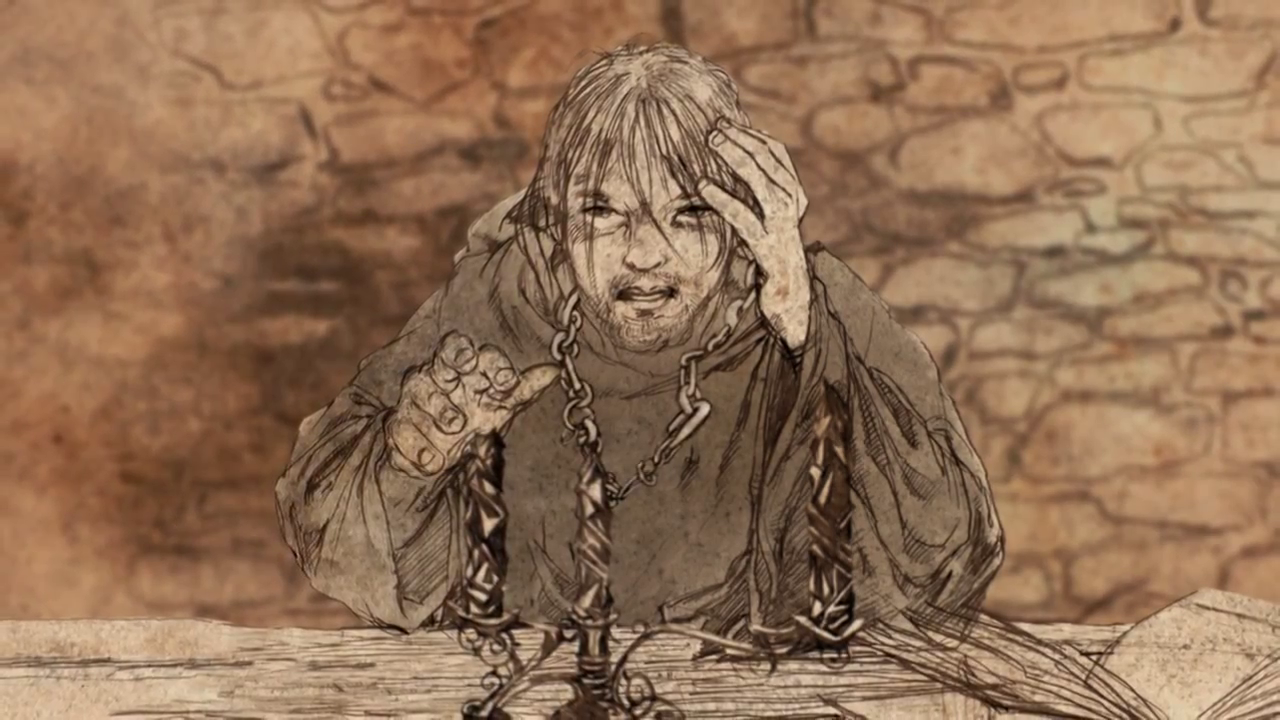

"The night before an acolyte says his vows, he must stand a vigil in the vault. No lantern is permitted him, no torch, no lamp, no taper . . . only a candle of obsidian. He must spend the night in darkness, unless he can light that candle. Some will try. The foolish and the stubborn, those who have made a study of these so-called higher mysteries. Often they cut their fingers, for the ridges on the candles are said to be as sharp as razors. Then, with bloody hands, they must wait upon the dawn, brooding on their failure. Wiser men simply go to sleep, or spend their night in prayer, but every year there are always a few who must try."

". . . what's the use of a candle that casts no light?"

That stopped me in my tracks. I read it again. And then once more. And I wished that (or something like it, since we have neither dragons nor dragon glass in 21st-century America) had been our last lesson, perhaps the night before our hooding ceremony, since we don't don chains like the maesters of Westeros."It is a lesson," Armen said, "the last lesson we must learn before we don our

maestcr's chains. The glass candle is meant to represent truth and learning,

rare and beautiful and fragile things. It is made in the shape of a candle to

remind us that a maester must cast light wherever he serves, and it is sharp to

remind us that knowledge can be dangerous. Wise men may grow arrogant in their wisdom, but a maester must alwavs remain humble. The glass candle reminds us of that as well. Even after he has said his vow and donned his chain and gone forth to serve, a maester will think back on the darkness of his vigil and remember how nothing that he did could make the candle burn. . . for even with knowledge, some things are not possible."

How I wish they'd taught us how to simply sit with the dark.

I have been a therapist for 33 years, and in that time I have seen many who have grown arrogant--in their knowledge, if not their wisdom. I have seen a few use their knowledge in dangerous ways. And I have seen not a few who think that because they have the terminal degree, they must know everything. I have known psychologists trained in the scientist/practitioner tradition who abandoned all pretense at critical thinking the evening of the day they defended their dissertations. I have known psychologists who thought they had nothing else to learn and shut their minds to new ideas and new data. And I've met very few who didn't hold themselves above the less-educated. The whole profession has come to think of itself as wholly superior to masters-level practitioners, and spends a lot of time dissing them and expending energy defending turf from them that might be put to better use elsewhere. But that is another rant for another day.

Worse, and there is another rant coming on this one in a future post, psychology has come to believe that they have the power to change people. Therapy has become and "intervention" to be "delivered" as if to a retail consumer and its success is to be measured in "behavioral outcomes".

Our clients believe this, too, and will say to us, "What do we do about it?" or, "I am ready to be fixed, now." And when we can't, they ask us, "What is the use of a candle that casts no light?" So we are seduced into trying, only to bloody our fingers once more.

As the next passage in the Prologue to A Feast for Crows makes plain, the obsidian candle can give off light -- but that's not under our control.

"I know what I saw. The light was queer and bright, much brighter than any

beeswax or tallow- candle. It cast strange shadows and the flame never

flickered, not even when a draft blew through the open door behind me."

Armen crossed his arms. "Obsidian does not burn."

"Dragonglass.'' Pate said. "The smallfolk call it dragonglass." Somehow that seemed important.

"They do," mused Alleras, the Sphinx, "and if there are dragons in the world

again . . ."

"Dragons and darker things,'' said Leo.The dragonglass candle is in this sense a metaphor for healing, and gives another bit to the lesson Armen describes. Illness, unhappiness, neurosis--whatever you may wish to call it--is contained within us, and so is healing. There are things we may say or do, or not say or do in a session, things that grew out of our learning (not all of which is formal, by the way) that enter into a person in the same way that a maester's antidote enters the body to combat a poison, and we may contribute to a person's healing in that way. But in the same way that the antidote and the poison do battle inside the victim's body, with the body itself as one of the combatants, so, too, is psychological healing an inside job. We have very little power compared to what resides in you.

And powers far greater than either of us may determine whether that candle burns.